“Here is the book that every drama teacher should have on their shelf” – Sylvia Young, OBE

For a lesson that is an hour in length, you should be using about four to seven exercises.

For a well-balanced lesson, the teacher should take exercises from at least three or four different chapters. A well-balanced lesson might include one exercise from Chapter 1, ‘Relaxation and Focus’, one exercise from Chapter 2, ‘Voice’, one exercise from Chapter 3, ‘Movement’, one exercise from Chapter 4, ‘Unblocking Performers’ and two exercises from Chapter 6, ‘Objectives’.

Chapter 1: Relaxation and Focus

1.1 Releasing tension while lying down

A simple relaxation exercise in which students relax each body part, one body part at a time, while lying down.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Concentration, awareness, focus, relaxation and mindfulness.

Participants: This exercise can be done alone or in a group.

Time: 10–40 minutes (depending on the age group).

You’ll need: A warm room with a comfortable floor for students to lie on. If the room is cold, students should wear coats and/or use blankets to keep warm. If the floor is hard, students should lie on yoga mats or blankets.

How to: Ask the students to lie on the floor with their eyes closed. If the actor starts to feel sleepy during this exercise, they should open their eyes and try to bring the energy back into the body without moving; if they really need to, they can wiggle their toes or fingers to try and wake up.

Students need to try and bring their energy inwards, reclaiming it from others and different spaces, bringing their circle of attention in. Ask the students to notice the breath: is it slow, fast, steady, scattered? Is the breath in the chest, stomach or pelvic area? If it’s up in the chest, or even the throat, bring the breath down so that it’s lower in the body. The stomach, not the chest, should move up and down with each in- and out-breath.

Once the breath is stable, the actor can start relaxing each part of the body, one part at a time. They can start with softening the muscles in the forehead and then the eyebrows, the eyelids, the temples, the cheeks, the lips, the jaw, the tongue and any other parts of the face. It is important to spend a long time on the face as it’s one of the main areas people hold tension.

Once the actor has relaxed every part of the face, they can make very gentle ‘blah blah’ sounds, being careful to keep the tongue relaxed, as well as the face, as the sound is released. Once the actor has finished relaxing the face, they can move onto the body. Ask the students to start with the neck, allowing it to sink into the floor. Then they should drop the shoulders, noticing where the shoulders are in contact with the floor. Ask students to try and increase the contact with the floor by loosening into the ground: imagine the upper part of the body is melting into the floor. Next ask students to bring the attention to the hands, letting the fingers, thumbs, palms and wrists melt into the ground. Talk then through working the attention up into the arms, releasing the tension from the forearm, elbow and upper arm. Now ask them to work the attention down the body, releasing the mid back and lower back, relaxing the abdominal muscles and then moving onto the lower body.

Explain that people vary – some tend to carry most of their tension in the lower body, others in the upper body and others in isolated areas such as the eyelids or jaw. Ask students to reflect on where they hold their tension.

For the relaxation of the lower body, the actor can start by wiggling their toes and then relax the toes, the feet, the calf muscles, quad muscles, hamstrings, pelvis and buttocks. Once every part of the body has been relaxed, ask the actor to imagine energy flowing in through the feet, up the legs, through the hips, up into the upper body and face. Allow this energy to move freely through the body with no blockages of tension. Allow a good few minutes for this sensation to arise, and when it is time to stand up, make sure the students really take their time; firstly you don’t want them to get dizzy. But secondly it’s important to keep the relaxation that was just achieved in the body while standing up.

Variation: It’s also possible to do this exercise standing up with the back against a wall, or standing with no support or sitting down. If practising this exercise standing up, it’s important to keep the feet hip-width apart.

Tip: Students shouldn’t rush this exercise but take their time as they relax every part of the body. Anxieties and thoughts should be left outside of the rehearsal space.

The aim: For the actor to become more aware of their body and face, exploring where it is they are prone to holding tension and then releasing this.

Chapter 2: Voice

2.2 Diction and tongue-twisters

Vocal exercises to help students with speech and projection.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Voice, diction, speech and projection. Participants: This exercise can be done alone or in a group.

Time: 5–15 minutes.

You’ll need: A space for students to stand in a circle.

How to: Ask students to stand in a circle and to check their posture. The feet should be hip-width apart and the spine pulled up gently from the tip of the head. Start the warm-up by asking the students to open their mouths really wide and then quickly scrunch their lips up into a really tight prune shape. Repeat opening and closing the mouth like this three or four times. Now ask the students to place their hands on their diaphragms. With the in-breath the diaphragm pushes out the hand and with the out-breath the diaphragm contracts. Ask the students to think of their diaphragm as a balloon: with the in-breath the balloon blows up, filling with air, and with the out-breath the air is released, making the balloon shrink. After a few of these deep breaths in and out, ask the students to make a humming sound on the out-breath. Breathe in together to the count of three, expanding the diaphragm, and breathe out on a hum to the count of six. Explain to the students that they should choose one note and that sound should come from deep down in the pelvic area. This humming noise should vibrate the torso and lips; if it’s not doing so, ask the students to hum a little louder and deeper.

Now explain to the students that diction is very important, particularly in theatre work. Good diction will help the audience to hear and understand the actor. I find that diction is particularly a problem with younger students. For good diction, explain that consonants need to be pronounced very clearly at the beginning and end of each word. The 21 consonant letters in the English alphabet are b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, x, z and usually w and y. Say a consonant, for example, ‘b, b, b, b’, and then ask the students to say it with you, ‘b, b, b, b’. Do this for at least five or six constants, or go through all of them if the class is older and focused. Now do the same for some constant sounds such as ch, sh and th. Now move onto some words that start and end in a consonant, asking students to really emphasize pronouncing the letters. Some examples include bed, sack, hat, tall, Bob, fizz, frozen and Jack.

After this group warm-up, give the group some tongue-twisters to work on; these can be said as a group altogether or in smaller groups. Once the group knows each other well, you can ask students to say a tongue-twister on their own in front of the group; however, they must never be forced to do this.

Tongue-twisters:

Red lorry, yellow lorry.

Red lorry, yellow lorry.

Red lorry, yellow lorry.

Red lorry, yellow lorry. …

She sells sea shells on the sea shore.

She sells sea shells on the sea shore.

She sells sea shells on the sea shore.

She sells sea shells on the sea shore. …

Round and round the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran.

Round and round the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran.

Round and round the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran.

Round and round the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran. …

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream.

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream.

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream.

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream. …

Toy boat.

Toy boat.

Toy boat.

Toy boat. …

A proper copper coffee pot.

A proper copper coffee pot.

A proper copper coffee pot.

A proper copper coffee pot. …

Unique New York.

Unique New York.

Unique New York.

Unique New York. …

A big black bear ate a big black bug.

A big black bear ate a big black bug.

A big black bear ate a big black bug.

A big black bear ate a big black bug. …

Eleven benevolent elephants.

Eleven benevolent elephants.

Eleven benevolent elephants.

Eleven benevolent elephants.

Variation: You can ask the students to invent some of their own tongue-twisters.

Tip: Listen and learn from news readers, theatre actors, good public speakers (and fingers-crossed drama teachers!) to hear how they use their voices to communicate clearly.

The aim: To help students to speak with good diction.

Chapter 3: Movement

3.2 Elbow to elbow

A simple physical warm-up exercise.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Movement, energy, spatial awareness and group awareness.

Participants: Needs to be done in a group of five or more.

Time: 5–10 minutes. You’ll need: A room big enough for students to walk around in at a fast pace.

How to: The students walk around the room at a brisk speed, making sure they don’t bump into anyone or anything. Encourage the students to use up all of the space in the room and to change direction frequently. The teacher will call out a body part. Let’s say ‘elbow’ to start with, and the students run towards someone and touch their elbow to someone else’s elbow. This doesn’t have to be done in pairs; there can be groups of three or more touching elbows, although you will find the group will naturally gravitate into pairs. After everyone has found an elbow to touch their elbow with, the teacher calls ‘go’ and the students walk around the room again. After a few moments, the teacher calls out another body part – hand, for example – and the students race to touch their hand to someone else’s hand. Good body parts to call include knee, hand, thumb, foot, shoulder, back, little finger, wrist and ankle. Be careful not to call out any inappropriate body parts.

Tip: Don’t let anyone feel left out in this game. If someone is hovering around feeling like they can’t join a pair who are already touching elbows, encourage them to go over and make a three. This game is about inclusion, not exclusion.

The aim: To warm students up physically.

Chapter 4: Unblocking Performers

4.4 Yes, let’s!

A fast-paced group improvisation exercise.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Listening, spontaneity, imagination and improvisation.

Participants: This exercise needs to be practised in a group of five or more.

Time: 5–10 minutes.

You’ll need: A space big enough for students to walk around in.

How to: Ask the students to stand in a space in the room and then initiate an

action by saying something like ‘Let’s bake a cake.’ Ask the class to reply with

‘Yes, let’s!’ and then they will all pretend to bake a cake. The students can

shout out any idea they like; nothing is too crazy. Perhaps someone might

call out:

‘Let’s wash a lion!’

‘Yes, let’s!’ the class will call out.

And everyone will wash a lion.

Then someone might call, ‘Let’s all be aeroplanes.’

‘Yes, let’s!’ the class will call out.

And everyone will pretend to be aeroplanes. The game continues like this.

Theming: This game can be themed. Let’s imagine that you are leading a fairytale workshop. In this case, the game could be played as above, but instead

of the suggestions being random, they are suggestions which meet the theme

fairy tales. For example, someone might say, ‘Let’s all climb a beanstalk.’ The

class is to reply with ‘Yes, let’s!’ and then they will all pretend to climb a

beanstalk. The students can shout out any idea they like; nothing is too crazy,

but ask them to keep to the fairy-tale theme. Perhaps someone else might

call out:

‘Let’s blow down the little pig’s house.’

‘Yes, let’s!’ the class will call out.

And everyone will blow down the little pig’s house.

Then someone might call, ‘Let’s clean the fireplace.’

‘Yes, let’s!’ the class will call out.

And everyone will pretend to clean the fireplace. The game continues like this.

Tip: For younger students or/and groups that are lively, it’s a good idea for the

teacher to stop the class with a signal for silence and then ask students to put

their hands up if they have a suggestion for the next ‘Yes, let’s!’ idea. This way

the student calling the idea will be heard and a mixture of students will get to

make suggestions. Encourage the quieter members of the group to contribute

ideas too.

The aim: For all improvisation ideas to be accepted and acted on with the aim of

loosening up students and creating a space where they feel safe to improvise in

Chapter 6: Objectives

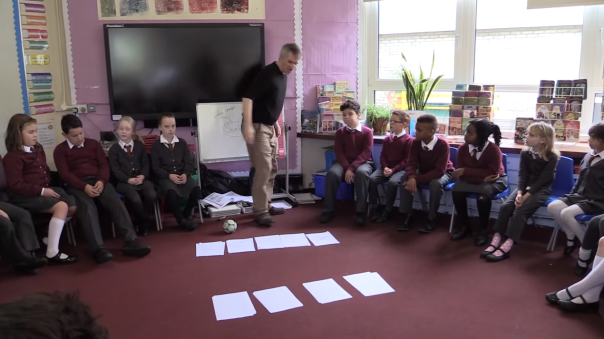

6.5 Objectives with props

A fun verbal reasoning exercise where students try to convince the group why they need an object the most.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Communicative skills, verbal reasoning, persuasion, lateral thinking and intuition. Participants: For a group of five or more.

Time: 10–15 minutes.

You’ll need: Anything between five and twenty props laid down in the centre of a circle of students. These props can be absolutely anything, but a variety is good. For example, a helmet, wooden spoon, scarf, mask, teddy bear, candle, coat, thermometer, headphones and yoga mat.

How to: The class sit in a circle, and in the centre of the circle, there is a collection of props. As explained above, this can be a collection of random objects. One student will then go to the centre of the circle, pick up one of these objects and explain to the circle of students around them why they really need that object. The person explaining needs to imagine that the class doesn’t want them to have the object. The actor has to try really hard to talk the group into letting them have the object. For example, if Chen were in the centre of the circle and she picked up a doll, she would need to convince the class to let her have this doll. She can think of any made-up reason she likes. Perhaps she could explain that she really needs it for her little sister as her sister is in hospital and the doll will cheer her up. Or Chen might explain that this is her long-lost doll from childhood and she lost it on holiday when she was four. It’s Chen’s objective to make the class say yes she can have the object. Once Chen has finished her story, the class can respond with yes or no.

Students can make the stories as elaborate as they like; if Chen were feeling adventurous, she could say the doll belongs to an enchanted empress and that if the class doesn’t let Chen have it, she can take it back to the rightful owner and the empress will cast a terrible spell on the group!

Tip: Encourage students to make eye contact with the people in the circle as a means to get what they want.

The aim: For students to think laterally and improve their persuasion skills.

6.4 Group improvisation with objectives

In groups, students create a short improvisation where each character has a strong objective.

Age: 8 plus.

Skills: Improvisation, teamwork, creating a character and communicative skills. Participants: This needs to be practised in groups of three or four.

Time: 20–25 minutes. You’ll need: A space big enough for students to rehearse.

How to: Ask the students to get into groups of three or four. Explain that they are going to create a 5-minute improvisation. In this improvisation, each character must have one want, and this want can be anything: to go to the moon, to have an ice cream, to be a world-famous skate boarder. Once each actor has thought up an objective; ask the group to agree on a setting for their improvisation. A public space works best, such as a park bench, doctor’s waiting room, art gallery, airport or bus stop.

Give the students about 10 minutes to practise an improvisation with those three or four characters together with their strong objectives in a public space. Once the 10 minutes is up, ask the students to show the improvisation to the rest of the class, and the audience can try and guess the characters’ objectives.

Tip: Each actor should only play one objective. Simple objectives are acceptable; sometimes it’s the simple ones that are the most effective. Something like ‘wants to do their coat up (but the zip’s broken)’ is enough.

The aim: For students to create a group improvisation where objectives take centre stage and to show students that objectives are a great way to create conflict and action within a scene.

This is an extract from Samantha Marsden’s new book 100 Acting Exercises for 8-18 Year Olds. It is available to buy now.

Samantha Marsden studied method acting at The Method Studio in London. She worked as a freelance drama teacher for eleven years at theatre companies, youth theatres, private schools, state schools, special schools and weekend theatre schools. In 2012, she set up her own youth theatre, which quickly grew into one of the largest regional youth theatres in the country. Follow her on Twitter @SamMarsdenDrama

natural for children to have some anxieties. That’s why schools normally put a lot of work into helping with the transition. But these are not normal times.

natural for children to have some anxieties. That’s why schools normally put a lot of work into helping with the transition. But these are not normal times. Knowledge is power, and even in these difficult times, transition years teachers will make sure children have all the general information they need, such as the different ways classes are organised and delivered in secondary schools. But talking to children about their individual concerns can uncover specific worries that might seem surprising.

Knowledge is power, and even in these difficult times, transition years teachers will make sure children have all the general information they need, such as the different ways classes are organised and delivered in secondary schools. But talking to children about their individual concerns can uncover specific worries that might seem surprising.

hundred fiction and non-fiction children’s titles, including Finding Fizz and the Peony Pinker series. Jenny always wanted to be an author and learnt the craft of writing in the couple of years that she worked for educational publishers. She has written prolifically on the theme of bullying and her books have been translated into many languages: German, Danish, Welsh, Portuguese, Greek, Indonesian, Chinese, Korean and Turkish.

hundred fiction and non-fiction children’s titles, including Finding Fizz and the Peony Pinker series. Jenny always wanted to be an author and learnt the craft of writing in the couple of years that she worked for educational publishers. She has written prolifically on the theme of bullying and her books have been translated into many languages: German, Danish, Welsh, Portuguese, Greek, Indonesian, Chinese, Korean and Turkish.

Unable to source relevant training at primary level I devised an LGBT+ inclusion teacher training programme, delivering it to over one hundred staff. I also sourced books for our classrooms about diverse identities, including ‘Daddy’s Roommate’ the very same book that had once moved me to tears.

Unable to source relevant training at primary level I devised an LGBT+ inclusion teacher training programme, delivering it to over one hundred staff. I also sourced books for our classrooms about diverse identities, including ‘Daddy’s Roommate’ the very same book that had once moved me to tears. progressing, and I knew this one was going to be all right. I’m not usually boastful about what I do, but I’ve decided to emulate Widsith and say that I think

progressing, and I knew this one was going to be all right. I’m not usually boastful about what I do, but I’ve decided to emulate Widsith and say that I think